A – I’ll admit that I too wondered the same thing as a young runner and I even experimented with trying to stride what I thought was the same way as the long distance stars of the day like Jerome Drayton, Bill Rodgers, etc.

And on winter days, when say an inch of fresh fallen snow was on the ground, I would examine my stride pattern (just tell passersby you’re looking for a contact lens). Also, this is one way to compare the length of the left vs. right leg strides -asymmetry may also indicate muscle strength imbalance (see my article HERE).

But trying to imitate other runners is dicey. After all, one’s form is affected by posture, joint angles, foot strike, muscle strength and coordination, body composition and is also dependent on skeletal proportions And any change in any of these parameters will affect stride patterns. And obviously, body growth associated with maturing from a young teen to an adult can have a major impact.

My own experimentation, between the extremes of really exaggerating the length of my stride (almost leaping or extending/reaching my lower leg out in front of me), versus taking much shorter strides, felt like far more effort at any given pace.

But it only makes common sense that the best stride length would be somewhere in between. But where...?

I’m betting you’ve already Googled or Binged (does anyone Bing?) this subject and seen that there’s a load of articles in the popular mags. But for your interest, I’ll share with you two relevant scientific studies that were conducted 35 years apart.

So the first was in 1982, and documented in a paper titled

The effect of stride length variation on oxygen uptake during distance running Med Sci Sports Exerc.1982;14(1):30-5.

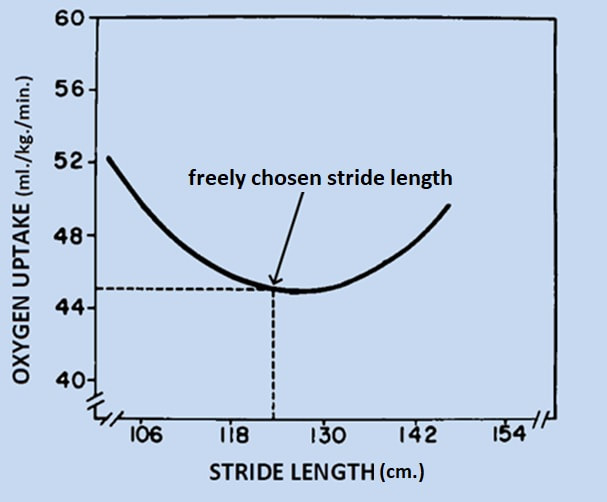

10 very fit, male runners were the subjects These dudes were made to run on a treadmill at a speed of 7:00 min. per mile (approx. 4:22/km.) while their oxygen consumption (uptake) and their freely chosen stride lengths were measured.

The runners were then observed running at the same speed, while being instructed to stride in time with the beat of a metronome. The metronome was set at frequencies which were slower and faster than their naturally chosen stride frequency, making their strides longer or shorter.

And the result? Well, less oxygen was used at their naturally chosen stride length. As an example, the graph below shows the results observed on one of the runners - and this pattern was typical of the entire group.

The 2017 Study

The second more recent study was published in 2017, titled:

Self-optimization of Stride Length Among Experienced and Inexperienced Runners Int J Exerc Sci. 2017; 10(3): 446–453.

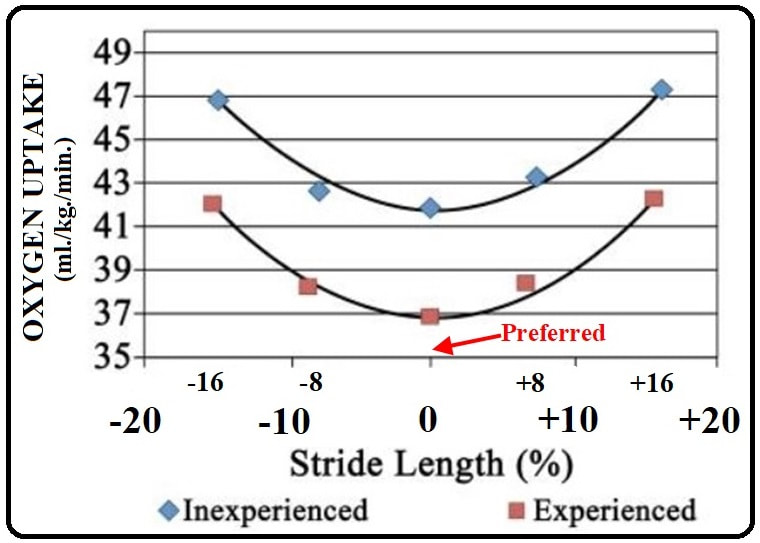

This study aimed to determine whether stride self-economization is different between "experienced" runners, who averaged at least 20 miles per week, and "inexperienced" runners, who never ran more than 5 miles/wk. in their lives. All subjects were from a university population.

As in the 1982 study, a metronome was used to direct/force the participants to run with five different stride lengths:

1) preferred

2) plus 8 % of preferred

3) plus 16% of preferred

4) minus 8% of preferred

5) minus 16% of preferred

The experienced runners ran 3.66m/sec. which = 400m in 1:49 pace or about 7:20 per mile. The inexperienced runners ran 3.04m/sec. which = 400m in 2:11 pace, or about 8:49 per mile.

Basically, the results were similar to the 1982 study as indicated in the graph below, i.e., inexperienced runners are equally capable of optimizing stride length for minimal oxygen uptake as experienced runners.

Takeaways

Both studies clearly indicate that runners generally adopt a stride length and frequency that's the most economical regardless of running speed they're running at.

So it would seem that the body/mind naturally adjusts the stride length and frequency to whatever speed is asked of it, so as to minimize effort. Call it Self-Economization.

This Self-Economization is consistent with a fundamental survival instinct called HOMEOSTASIS which, refers to our body's ongoing efforts to reduce any undue discomfort.

(Check out Homeostasis: The Underappreciated and Far Too Often Ignored Central Organizing Principle of Physiology Front. Physiol., 10 March 2020)

Now the authors of the 2nd study wrote “athletes and coaches do not need to alter runner’s stride length when economy is the main concern.”

However I must suggest a caveat to this statement. That is, you may want to indirectly foster a change of stride length if running form is obviously less than ideal ?

For fun check out some of the less than ideal running forms in the youtube video below (BTW, I have never seen a study that looked at running economy before and after a change of running form).

After all, the form may be jerkily uncoordinated - or asymmetrical, as a consequence of past injuries that have conciously or unconconciouly caused adjustments to reduce/protect from pain. (see also HERE)

Anyway, an improvement of running form is likely going to impact on stride length. But if so, it will also likely be the most economical.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed