The following article appeared in the online version of The Globe and Mail May 5, 2017

_________________________________________________________________________

Ed Whitlock the tortoise, Earl Fee the hare and the run of their lives

In their 80s, two men both raced into sports history. Bruce Grierson discerns what we can learn from their roads to fitness

____________________________________________________________________

BRUCE GRIERSON

SPECIAL TO THE GLOBE AND MAIL

LAST UPDATED: FRIDAY, MAY 05, 2017 12:54PM EDT

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

BRUCE GRIERSON

SPECIAL TO THE GLOBE AND MAIL

LAST UPDATED: FRIDAY, MAY 05, 2017 12:54PM EDT

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

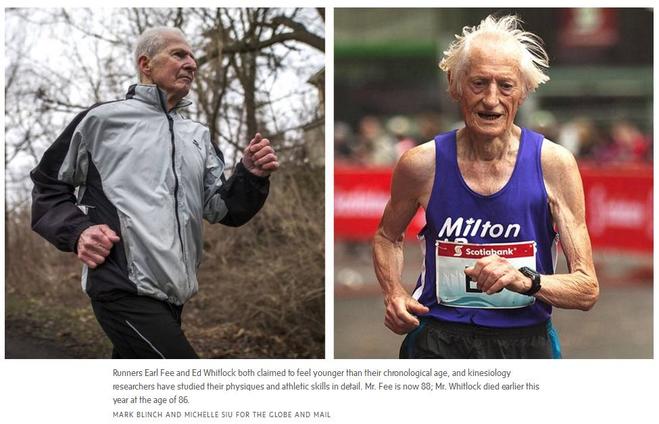

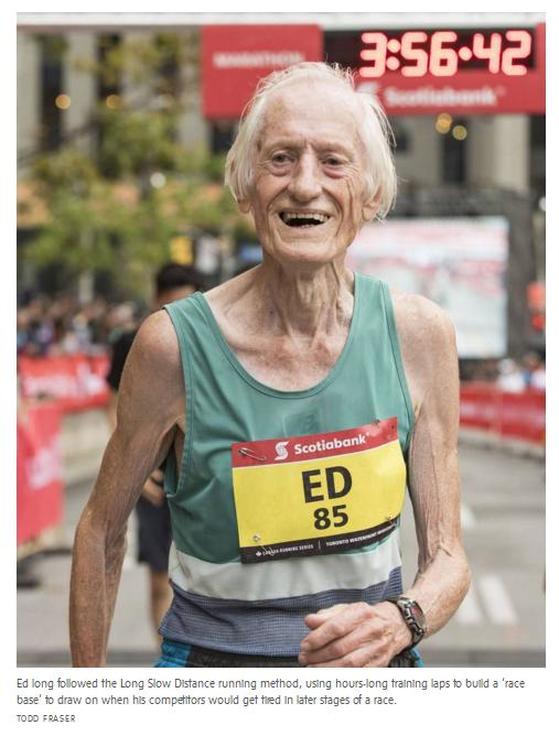

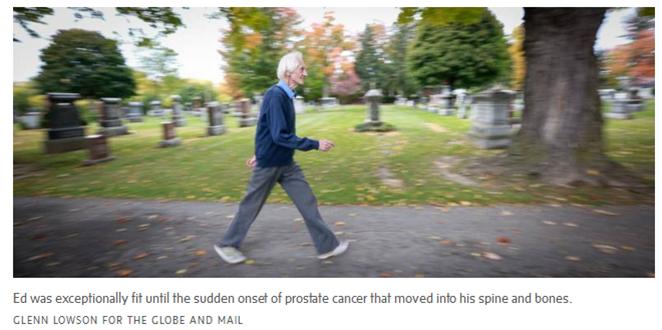

Ed Whitlock, a quiet gentleman of wry British wit, an iron will and a body seemingly purpose-built to run marathons, held 36 age-group world records. He was the oldest person ever to run a marathon in under four hours, and the only person aged 70 or over ever to run a marathon in under three hours. “Ed was really my hero,” said Earl Fee, two days after attending Ed’s funeral in Milton, Ont., just west of Toronto. On March 13, Ed succumbed to a cancer only his close friends and family knew he was battling. He was 86.

Earl, who turned 88 in March, is similarly decorated in his own, shorter-distance events. He holds 15 World Masters Athletics world records. At age 66, in Buffalo, he ran 800 metres in 2:14 seconds, so demolishing the world record that officials drug-tested him twice. He is one of so few runners his age who still does hurdles that at the world championships in Costa Rica three years ago, there was no one for him to run against. So race organizers ended up pitting him against world-champion sprinter Christa Bortignon from West Vancouver, then 77. (Earl led for the entire 200-metre race, but Christa pipped him at the post. She leaned in.)

Ed and Earl, Earl and Ed. Two white guys of similar vintage and background – both loners; coincidentally, both engineers – who ran their way into sports history at an age when most of us are comparison-shopping for walkers, if we’re lucky . The two friends present a kind of natural experiment. For beyond these base traits that throw them in the same sample hopper, they are a study in contrasts – and the differences may be telling.

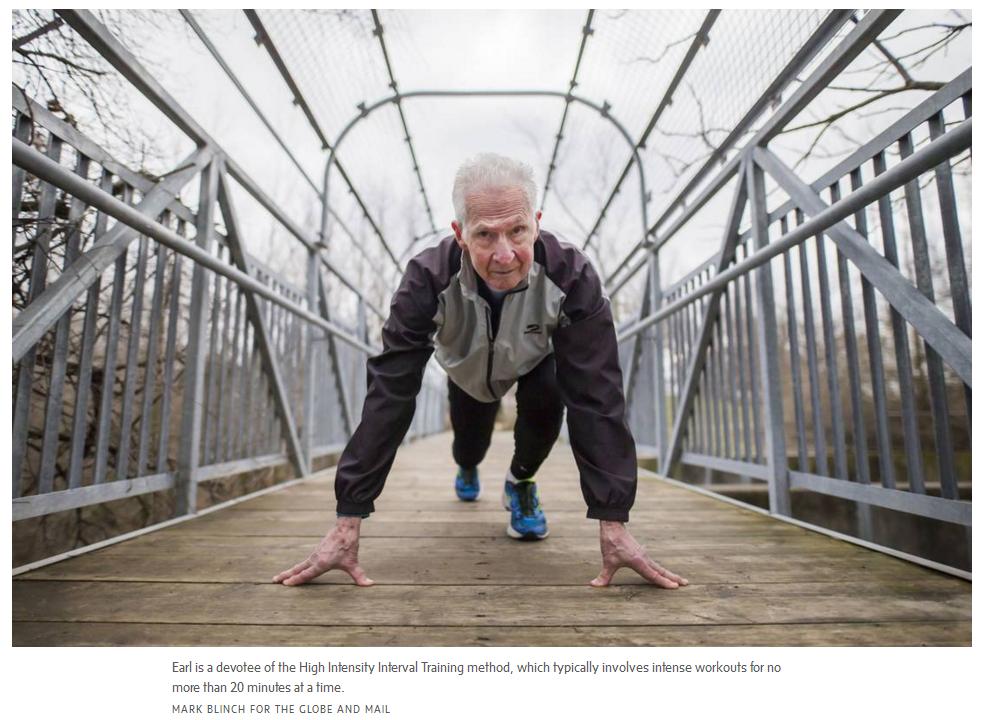

Earl is a devotee of HIIT – High Intensity Interval Training. He hardly ever works out for more than 20 minutes at a time, but he makes those 20 minutes count. He goes for it, typically in a series of sprint bursts – between short breaks – that leave him gasping for air. He is fastidious in his training habits – timing his intervals, salting in weight-lifting and cross-training, tweaking his regimen according to the evolving sports science. What’s more, he gets fairly frequent medical consults, eats half a pound of steamed vegetables with dinner, and takes six supplements.

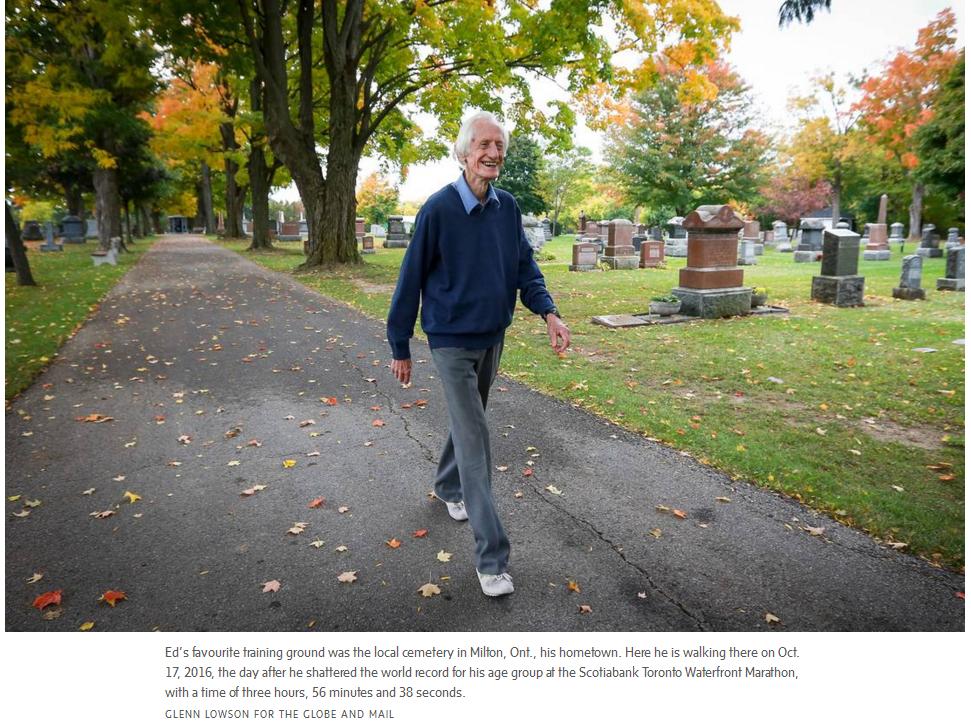

Ed had long followed a program of LSD – Long Slow Distance running. He tallied endless training laps under Evergreen Cemetery’s tree canopy, patiently building a “race base” – “drudgery,” he called it, but all that mileage was money in the bank which he could draw on round about mile 22, when other guys were crashing. In 2004, in the run-up to the Toronto marathon, Ed put in three-hour training runs, more days than not, for months. Then he duly turned in what was arguably the greatest marathon ever run – 2:54:48, in Toronto, at age 73. Decidedly unfastidious in his training habits, he sometimes stretched on race day, and had seen his family doctor for a check-up exactly once since Trudeau came to office – Pierre Elliott Trudeau. His diet? Ed ate “whatever they’re serving,” he once told me. At meets, he sometimes seemed to subsist on coffee and grilled-cheese sandwiches.

Ed and Earl, Earl and Ed. They were, in a sense, the hare and the tortoise. And their approach to fitness may hold lessons for the rest of us mere mortals – who aren’t aiming to topple world records, just trying to stay young – whether our working definition of that is hanging on to our muscles or our marbles or our sex drive, or even, potentially, keeping cancer at bay.

_________________________________________________________________________

Earl, who turned 88 in March, is similarly decorated in his own, shorter-distance events. He holds 15 World Masters Athletics world records. At age 66, in Buffalo, he ran 800 metres in 2:14 seconds, so demolishing the world record that officials drug-tested him twice. He is one of so few runners his age who still does hurdles that at the world championships in Costa Rica three years ago, there was no one for him to run against. So race organizers ended up pitting him against world-champion sprinter Christa Bortignon from West Vancouver, then 77. (Earl led for the entire 200-metre race, but Christa pipped him at the post. She leaned in.)

Ed and Earl, Earl and Ed. Two white guys of similar vintage and background – both loners; coincidentally, both engineers – who ran their way into sports history at an age when most of us are comparison-shopping for walkers, if we’re lucky . The two friends present a kind of natural experiment. For beyond these base traits that throw them in the same sample hopper, they are a study in contrasts – and the differences may be telling.

Earl is a devotee of HIIT – High Intensity Interval Training. He hardly ever works out for more than 20 minutes at a time, but he makes those 20 minutes count. He goes for it, typically in a series of sprint bursts – between short breaks – that leave him gasping for air. He is fastidious in his training habits – timing his intervals, salting in weight-lifting and cross-training, tweaking his regimen according to the evolving sports science. What’s more, he gets fairly frequent medical consults, eats half a pound of steamed vegetables with dinner, and takes six supplements.

Ed had long followed a program of LSD – Long Slow Distance running. He tallied endless training laps under Evergreen Cemetery’s tree canopy, patiently building a “race base” – “drudgery,” he called it, but all that mileage was money in the bank which he could draw on round about mile 22, when other guys were crashing. In 2004, in the run-up to the Toronto marathon, Ed put in three-hour training runs, more days than not, for months. Then he duly turned in what was arguably the greatest marathon ever run – 2:54:48, in Toronto, at age 73. Decidedly unfastidious in his training habits, he sometimes stretched on race day, and had seen his family doctor for a check-up exactly once since Trudeau came to office – Pierre Elliott Trudeau. His diet? Ed ate “whatever they’re serving,” he once told me. At meets, he sometimes seemed to subsist on coffee and grilled-cheese sandwiches.

Ed and Earl, Earl and Ed. They were, in a sense, the hare and the tortoise. And their approach to fitness may hold lessons for the rest of us mere mortals – who aren’t aiming to topple world records, just trying to stay young – whether our working definition of that is hanging on to our muscles or our marbles or our sex drive, or even, potentially, keeping cancer at bay.

_________________________________________________________________________

Youthfulness, Part 1: In their only laboratory matchup, Ed takes the lead

Certainly Ed looked older than Earl – at least off the track. But when the starting gun cracked and he broke into a run, he became almost supernaturally youthful, gliding so gracefully, so gossamer-lightly, he looked as if he could run through freshly poured cement without leaving a mark. Earl is all power on the track, but no less “youthful” for that. On appearances alone, you could call it a wash.

But was Ed younger on the inside? Or was Earl? To get a bead on that, it won’t do to look from the outside in. You have to look from the inside out.

In 2012, Tanja Taivassalo and Russell Hepple, then kinesiology professors at McGill (both are now at the University of Florida) did just that. As part of what has become known as the McGill Masters Study, involving more than two dozen participants, aged 75 to 93, they invited Ed and Earl separately into their lab. This allowed for a rare head-to-head comparison of the two athletes, who along with their fellow subjects were submitted to a battery of tests that assessed everything from cardiovascular health to muscle composition, flexibility to brain density.

Unsurprisingly, both men crushed it. More surprising, given the differences in the way they lived and trained, was that their “numbers” were often pretty similar. Both had roughly twice the mitochondria in their muscle cells as did the sedentary controls. That means twice the ability to suck in fuels such as glucose and fat, to make energy – and twice the anti-inflammatory protection against chronic disease in the bargain.

Both men also had NASCAR engines in their chests. Ed’s heart showed no signs of the hypertrophy (dangerously enlarged left ventricle) or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) that ultra-distance runners are often heir to. His blood pressure was a little high, but that was no surprise to him. “My own theory is that my heart is a bit too strong,” Ed once told me – the pushing power maybe exceeded the width of the plumbing in there, he ventured. “Or it could just be all the salt in my diet.” (Indeed, it is Earl, not Ed, who has inexplicably developed a heart hiccup in latter years. He has tachycardia, a scary condition that can cause the heart to rev for no apparent reason. The times that happens, he says, are the only times he feels his age.)

At one point in the McGill testing, Ed and Earl were ushered into a hospital room, and a scientist brandished a gleaming instrument that looked a bit like a wine corker. He extracted a little plug of muscle from each man’s thigh. (Earl, particularly, had some trouble recovering from that procedure. Back in Toronto, he visited the storied sports-medicine doctor Anthony Galea, who fashioned a little artificial divot out of Earl’s own blood plasma, and plugged the hole with it, to speed healing.) Earl, it turned out, had somewhat more “fast-twitch” fibres in his leg – which provide explosive power, but fatigue faster – than Ed. That’s understandable, since he’s a sprinter and Ed was a distance man. Fast-twitch muscle ratio could be considered a metric of youthfulness: We are young, one might argue, to the degree that we can really bring it on when we need to – even if that just means sprinting for the bus. Then again, endurance may also signal “fitness,” at least in the Darwinian sense: Back on the veldt, it may have been the most important attribute of all.

The biggest difference was their VO2 max scores. That’s a measure of the highest rate that the body can take up and use oxygen. Earl’s score was high. But Ed’s score was literally off the charts – the highest ever recorded for someone his age. VO2 max scores correlate not just with longevity but with basic health – youthfulness, if you like. So much so that a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last month suggested that one’s VO2 max score should be considered a vital sign, as basic as blood pressure or pulse.

Score a point for Ed.

_________________________________________________________________________

Certainly Ed looked older than Earl – at least off the track. But when the starting gun cracked and he broke into a run, he became almost supernaturally youthful, gliding so gracefully, so gossamer-lightly, he looked as if he could run through freshly poured cement without leaving a mark. Earl is all power on the track, but no less “youthful” for that. On appearances alone, you could call it a wash.

But was Ed younger on the inside? Or was Earl? To get a bead on that, it won’t do to look from the outside in. You have to look from the inside out.

In 2012, Tanja Taivassalo and Russell Hepple, then kinesiology professors at McGill (both are now at the University of Florida) did just that. As part of what has become known as the McGill Masters Study, involving more than two dozen participants, aged 75 to 93, they invited Ed and Earl separately into their lab. This allowed for a rare head-to-head comparison of the two athletes, who along with their fellow subjects were submitted to a battery of tests that assessed everything from cardiovascular health to muscle composition, flexibility to brain density.

Unsurprisingly, both men crushed it. More surprising, given the differences in the way they lived and trained, was that their “numbers” were often pretty similar. Both had roughly twice the mitochondria in their muscle cells as did the sedentary controls. That means twice the ability to suck in fuels such as glucose and fat, to make energy – and twice the anti-inflammatory protection against chronic disease in the bargain.

Both men also had NASCAR engines in their chests. Ed’s heart showed no signs of the hypertrophy (dangerously enlarged left ventricle) or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) that ultra-distance runners are often heir to. His blood pressure was a little high, but that was no surprise to him. “My own theory is that my heart is a bit too strong,” Ed once told me – the pushing power maybe exceeded the width of the plumbing in there, he ventured. “Or it could just be all the salt in my diet.” (Indeed, it is Earl, not Ed, who has inexplicably developed a heart hiccup in latter years. He has tachycardia, a scary condition that can cause the heart to rev for no apparent reason. The times that happens, he says, are the only times he feels his age.)

At one point in the McGill testing, Ed and Earl were ushered into a hospital room, and a scientist brandished a gleaming instrument that looked a bit like a wine corker. He extracted a little plug of muscle from each man’s thigh. (Earl, particularly, had some trouble recovering from that procedure. Back in Toronto, he visited the storied sports-medicine doctor Anthony Galea, who fashioned a little artificial divot out of Earl’s own blood plasma, and plugged the hole with it, to speed healing.) Earl, it turned out, had somewhat more “fast-twitch” fibres in his leg – which provide explosive power, but fatigue faster – than Ed. That’s understandable, since he’s a sprinter and Ed was a distance man. Fast-twitch muscle ratio could be considered a metric of youthfulness: We are young, one might argue, to the degree that we can really bring it on when we need to – even if that just means sprinting for the bus. Then again, endurance may also signal “fitness,” at least in the Darwinian sense: Back on the veldt, it may have been the most important attribute of all.

The biggest difference was their VO2 max scores. That’s a measure of the highest rate that the body can take up and use oxygen. Earl’s score was high. But Ed’s score was literally off the charts – the highest ever recorded for someone his age. VO2 max scores correlate not just with longevity but with basic health – youthfulness, if you like. So much so that a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last month suggested that one’s VO2 max score should be considered a vital sign, as basic as blood pressure or pulse.

Score a point for Ed.

_________________________________________________________________________

Youthfulness, Part 2: Earl catches up

Not so fast, says HIIT devotee Earl: “I believe that to stay young, intensity of exercise is more important than volume.”

Until recently, evidence for that has been circumstantial at best. But last month, data emerged to give Earl’s assertion some real teeth. In a study published in the journal Cell Biology, researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., looked at how different kinds of exercise affect aging muscles at the cellular level. In one trial, three groups of older test subjects – 65 years and up – were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups.

The first group trained like Ed – long, lower-intensity sessions with no breaks. The second trained like Earl – pulses of shorter, harder effort. (The third group did weight training alone.) Biopsies revealed that both kinds of running changed those aging muscle cells – rejuvenating them, in effect – by producing more (and better quality) mitochondria while dialling up the activity levels in certain genes.

But the interval training rejuvenated those cells more than the long, slow aerobics did. The intensity seemed to be a tonic that undid some of the cellular damage that naturally occurs when we age.

Score a point for Earl.

_________________________________________________________________________

Not so fast, says HIIT devotee Earl: “I believe that to stay young, intensity of exercise is more important than volume.”

Until recently, evidence for that has been circumstantial at best. But last month, data emerged to give Earl’s assertion some real teeth. In a study published in the journal Cell Biology, researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., looked at how different kinds of exercise affect aging muscles at the cellular level. In one trial, three groups of older test subjects – 65 years and up – were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups.

The first group trained like Ed – long, lower-intensity sessions with no breaks. The second trained like Earl – pulses of shorter, harder effort. (The third group did weight training alone.) Biopsies revealed that both kinds of running changed those aging muscle cells – rejuvenating them, in effect – by producing more (and better quality) mitochondria while dialling up the activity levels in certain genes.

But the interval training rejuvenated those cells more than the long, slow aerobics did. The intensity seemed to be a tonic that undid some of the cellular damage that naturally occurs when we age.

Score a point for Earl.

_________________________________________________________________________

The brain: Ed surges ahead

One hallmark of how well we’re aging is what’s happening to us between the ears. How well are we managing practical things, such as recalling names at parties and remembering that we just put a full cup of coffee on the roof of the car? In our brain, that’s largely the job of the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped region in the centre that helps us make and consolidate memories.

We know that exercise beefs up the hippocampus. But recently, researchers from the University of Jyvaskyla in Finland wondered whether any particular kind of exercise is better at building this part of the brain. In a study on rats published last February inThe Journal of Physiology, they tested the effect of long, steady-state running (the Ed protocol) vs. interval training (the Earl protocol) vs. resistance training: weight-lifting. (The rats, if you’re wondering, pulled a weight up a ramp.)

The result? Both kinds of running grew new neurons in the rats’ hippocampus. But the Ed workout grew a lot more of them. The joggers’ hippocampus positively teemed with new neurons. The greater the distance the marathon rats travelled, the more neurons they grew. (Weight training alone, by the way, didn’t spark any neurogenesis at all.)

One point for Ed.

_________________________________________________________________________

One hallmark of how well we’re aging is what’s happening to us between the ears. How well are we managing practical things, such as recalling names at parties and remembering that we just put a full cup of coffee on the roof of the car? In our brain, that’s largely the job of the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped region in the centre that helps us make and consolidate memories.

We know that exercise beefs up the hippocampus. But recently, researchers from the University of Jyvaskyla in Finland wondered whether any particular kind of exercise is better at building this part of the brain. In a study on rats published last February inThe Journal of Physiology, they tested the effect of long, steady-state running (the Ed protocol) vs. interval training (the Earl protocol) vs. resistance training: weight-lifting. (The rats, if you’re wondering, pulled a weight up a ramp.)

The result? Both kinds of running grew new neurons in the rats’ hippocampus. But the Ed workout grew a lot more of them. The joggers’ hippocampus positively teemed with new neurons. The greater the distance the marathon rats travelled, the more neurons they grew. (Weight training alone, by the way, didn’t spark any neurogenesis at all.)

One point for Ed.

_________________________________________________________________________

Wear and tear: Earl pulls up to the side

What about plain old wear and tear on the body, surely another sign of how well we’re staving off the ravages of time? Turns out, intense interval training – the Earl Protocol – does create greater “impact forces”: sudden compression that puts strain on joints and tendons.

But there’s a coda. “If you’re working out for less time in total, maybe the cumulative loading on the joints is reduced,” says Martin Gibala, head of the kinesiology department at McMaster University in Hamilton, and author of The One Minute Workout. In other words, when you work out like Earl, your moving parts get a rest and your joints are spared the sort of relentless pummelling that keeps orthopedic surgeons in Caribbean vacations.

The data are not unanimous on this, but they tip Earl’s way. Ed, says the science, was an outlier. He could do what he did because he was Ed: a 107-pound package of awesome mechanics. (He dropped to 105 in November, but generally hovered around 110.) And even Ed felt the strain – he had chronic arthritis in his knees. And the main reason he ran his training runs (relatively) slowly, he once told me, was that “my Achilles hurts if I go faster.”

Point for Earl.

What about plain old wear and tear on the body, surely another sign of how well we’re staving off the ravages of time? Turns out, intense interval training – the Earl Protocol – does create greater “impact forces”: sudden compression that puts strain on joints and tendons.

But there’s a coda. “If you’re working out for less time in total, maybe the cumulative loading on the joints is reduced,” says Martin Gibala, head of the kinesiology department at McMaster University in Hamilton, and author of The One Minute Workout. In other words, when you work out like Earl, your moving parts get a rest and your joints are spared the sort of relentless pummelling that keeps orthopedic surgeons in Caribbean vacations.

The data are not unanimous on this, but they tip Earl’s way. Ed, says the science, was an outlier. He could do what he did because he was Ed: a 107-pound package of awesome mechanics. (He dropped to 105 in November, but generally hovered around 110.) And even Ed felt the strain – he had chronic arthritis in his knees. And the main reason he ran his training runs (relatively) slowly, he once told me, was that “my Achilles hurts if I go faster.”

Point for Earl.

_________________________________________________________________________

Life expectancy: It’s a tie

Running is good. On average, every hour you run lengthens your life by around seven hours, a recent meta-analysis found. Aerobic exercise stresses the body, mostly in a good way. True, it does goose the production of “free radicals” – highly reactive molecules that damage our DNA (and whose accumulation is, according to one theory, the most potent driver of human aging.) But exercise is both the snakebite and the antidote: Exercise itself is an anti-oxidant, mopping up the free radicals it creates, and then some. Almost always, the medicine trumps the venom.

Almost always. Could it be that there’s some tipping point at which aerobic exercise becomes so exhaustive that it stops being protective, and hastens aging more than it slows it? Could it be that all the “oxidative stress” that Ed was subjecting himself to, with all that mileage, was aging him faster than Earl’s 20-minutes-and-done workouts are aging him?

Again, the data are murky. “The idea that oxidative stress is bad, that’s a very challenging thing to sort out,” says Dr Hepple, of the McGill Masters Study. Some studies say it is. But when McGill biologist Siegfried Hekimi increased oxidative stress in his lab mice by letting them run and run and run on a wheel, he found the opposite: They aged more slowly. “If there is a tipping point” where exercise stops rejuvenating us and starts aging us, says Dr. Hepple, “we don’t know where it is.”

Ed and Earl each score a point.

_________________________________________________________________________

Life expectancy: It’s a tie

Running is good. On average, every hour you run lengthens your life by around seven hours, a recent meta-analysis found. Aerobic exercise stresses the body, mostly in a good way. True, it does goose the production of “free radicals” – highly reactive molecules that damage our DNA (and whose accumulation is, according to one theory, the most potent driver of human aging.) But exercise is both the snakebite and the antidote: Exercise itself is an anti-oxidant, mopping up the free radicals it creates, and then some. Almost always, the medicine trumps the venom.

Almost always. Could it be that there’s some tipping point at which aerobic exercise becomes so exhaustive that it stops being protective, and hastens aging more than it slows it? Could it be that all the “oxidative stress” that Ed was subjecting himself to, with all that mileage, was aging him faster than Earl’s 20-minutes-and-done workouts are aging him?

Again, the data are murky. “The idea that oxidative stress is bad, that’s a very challenging thing to sort out,” says Dr Hepple, of the McGill Masters Study. Some studies say it is. But when McGill biologist Siegfried Hekimi increased oxidative stress in his lab mice by letting them run and run and run on a wheel, he found the opposite: They aged more slowly. “If there is a tipping point” where exercise stops rejuvenating us and starts aging us, says Dr. Hepple, “we don’t know where it is.”

Ed and Earl each score a point.

_________________________________________________________________________

The cancer factor: No clear winner

Ed’s cancer diagnosis didn’t just surprise the grieving running community; it surprised Ed.

It wasn’t until last fall, around the time he was casually smashing the 15-kilometre world record for his age at a race in upstate New York, that Ed suspected something might be up. He was having trouble keeping weight on. Then, his shoulder hurt so much that he finally saw a doctor. The diagnosis: prostate cancer that, an MRI revealed, had moved into his spine and bones. “After that, things moved very quickly,” says his son Neil.

In a man with longevity in his family (his Uncle Arthur was actually Britain’s oldest man when he died at 108 in 2000), Ed’s death raises questions about the way he lived his life. Could there possibly be a link between the cancer and the training?

David Agus, a professor of medicine and engineering at the University of California, and a noted cancer specialist, is doubtful. “We know that there’s an association between some cancers and inflammation, but there’s no association we know of between strenuous exercise and prostate cancer,” he says. “Mutations happen. About half of the DNA changes in cancer just happen.”

In a 2008 study on potential links between exercise and cancer, scientists at Duke University in North Carolina found that prostate cancer grew twice as fast in mice that ran to their heart’s content as it did in sedentary mice. Exercise seemed to feed their tumours, perhaps by supplying more blood to them.

But that study comes with a very important caveat. “Those were human tumours that we planted in the mice,” notes Lee Jones, the clinical-exercise physiologist who headed that study. “The only way you can get a human tumour to grow in a mouse is if the mouse doesn’t have an immune system.” Exercise boosts the immune system, but it can’t work its magic if there’s no immune system to boost.

In a subsequent study, in which Dr. Jones’s team planted mouse breast-cancer tumours in mice – thus allowing the mice to keep their immune systems – the running rats showed the opposite result: Their tumours grew more slowly.

“If you live long enough as a man, you’re going to get prostate cancer,” Dr. Jones says. “Eighty per cent of men who are age 80 have prostate cancer. Seventy per cent of 70-year-old men have prostate cancer. The fact that Ed was 86, he probably had prostate cancer for years. But because he was in such a trained state, his body was very likely able to keep that cancer from spreading as long as it did.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quality of later life: Once again, a draw

We make a fetish of longer and longer life. But “lifespan” is not the most meaningful metric, argues Stephen Harridge, a respected physiologist at King’s College London. “Healthspan” is.

Actual time above ground means little if much of your Third Act takes place in the ICU. Something happens to our bodies around the eighth decade of life. Most of us tend to just start coming apart like a clock; afflictions compound, slowly choking off quality of life.

But for masters athletes, their slow, linear performance suddenly takes a discouragingly exponential plunge. Ed didn’t have “co-morbidity” issues. One single thing crept up on him right at the end. Like track-and-field legend Olga Kotelko, who died suddenly from a brain hemorrhage in the summer of 2015, just weeks after setting a passel of new world records at age 95, Ed was world-beatingly fit and feted – and then suddenly gone.

“Both of these folks” – Ed and Olga – “compressed their morbidity into a tiny, tiny fraction of their time on Earth,” says Dr. Hepple. And that might be the best definition of successful aging that we have. “Ever since Ed died,” adds Earl, “I’ve been thinking, it’s kind of a gift, what we do.”

In his heroically researched, 664-page book 100 Years Young the Natural Way he presents a kind of template for people to hit the century mark, following a protocol of exercise, stress reduction and strategic eating. Since the book came out in 2011, Earl has tweaked his diet a bit. He has almost entirely cut out fish and chicken, convinced by the data that vegetarians probably live longer. He avoids processed foods that create inflammation. He tends to his gut flora with foods such as sauerkraut and yogurt (although, he acknowledges, “some of that fermented food is not too tasty.”)

Will he justify his book’s title? He hopes so. “I’m still aiming for 100,” he says. “But life can be more fragile than you think.”

Ed’s cancer diagnosis didn’t just surprise the grieving running community; it surprised Ed.

It wasn’t until last fall, around the time he was casually smashing the 15-kilometre world record for his age at a race in upstate New York, that Ed suspected something might be up. He was having trouble keeping weight on. Then, his shoulder hurt so much that he finally saw a doctor. The diagnosis: prostate cancer that, an MRI revealed, had moved into his spine and bones. “After that, things moved very quickly,” says his son Neil.

In a man with longevity in his family (his Uncle Arthur was actually Britain’s oldest man when he died at 108 in 2000), Ed’s death raises questions about the way he lived his life. Could there possibly be a link between the cancer and the training?

David Agus, a professor of medicine and engineering at the University of California, and a noted cancer specialist, is doubtful. “We know that there’s an association between some cancers and inflammation, but there’s no association we know of between strenuous exercise and prostate cancer,” he says. “Mutations happen. About half of the DNA changes in cancer just happen.”

In a 2008 study on potential links between exercise and cancer, scientists at Duke University in North Carolina found that prostate cancer grew twice as fast in mice that ran to their heart’s content as it did in sedentary mice. Exercise seemed to feed their tumours, perhaps by supplying more blood to them.

But that study comes with a very important caveat. “Those were human tumours that we planted in the mice,” notes Lee Jones, the clinical-exercise physiologist who headed that study. “The only way you can get a human tumour to grow in a mouse is if the mouse doesn’t have an immune system.” Exercise boosts the immune system, but it can’t work its magic if there’s no immune system to boost.

In a subsequent study, in which Dr. Jones’s team planted mouse breast-cancer tumours in mice – thus allowing the mice to keep their immune systems – the running rats showed the opposite result: Their tumours grew more slowly.

“If you live long enough as a man, you’re going to get prostate cancer,” Dr. Jones says. “Eighty per cent of men who are age 80 have prostate cancer. Seventy per cent of 70-year-old men have prostate cancer. The fact that Ed was 86, he probably had prostate cancer for years. But because he was in such a trained state, his body was very likely able to keep that cancer from spreading as long as it did.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quality of later life: Once again, a draw

We make a fetish of longer and longer life. But “lifespan” is not the most meaningful metric, argues Stephen Harridge, a respected physiologist at King’s College London. “Healthspan” is.

Actual time above ground means little if much of your Third Act takes place in the ICU. Something happens to our bodies around the eighth decade of life. Most of us tend to just start coming apart like a clock; afflictions compound, slowly choking off quality of life.

But for masters athletes, their slow, linear performance suddenly takes a discouragingly exponential plunge. Ed didn’t have “co-morbidity” issues. One single thing crept up on him right at the end. Like track-and-field legend Olga Kotelko, who died suddenly from a brain hemorrhage in the summer of 2015, just weeks after setting a passel of new world records at age 95, Ed was world-beatingly fit and feted – and then suddenly gone.

“Both of these folks” – Ed and Olga – “compressed their morbidity into a tiny, tiny fraction of their time on Earth,” says Dr. Hepple. And that might be the best definition of successful aging that we have. “Ever since Ed died,” adds Earl, “I’ve been thinking, it’s kind of a gift, what we do.”

In his heroically researched, 664-page book 100 Years Young the Natural Way he presents a kind of template for people to hit the century mark, following a protocol of exercise, stress reduction and strategic eating. Since the book came out in 2011, Earl has tweaked his diet a bit. He has almost entirely cut out fish and chicken, convinced by the data that vegetarians probably live longer. He avoids processed foods that create inflammation. He tends to his gut flora with foods such as sauerkraut and yogurt (although, he acknowledges, “some of that fermented food is not too tasty.”)

Will he justify his book’s title? He hopes so. “I’m still aiming for 100,” he says. “But life can be more fragile than you think.”

_________________________________________________________________________

Bruce Grierson is the author, most recently, of What Makes Olga Run? He lives in North Vancouver.

Bruce Grierson is the author, most recently, of What Makes Olga Run? He lives in North Vancouver.